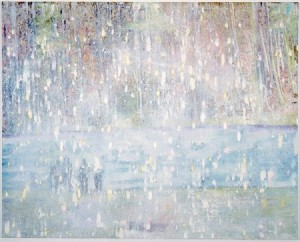

In a suitably snowy Montreal I went to see “No Foreign Lands”, an exhibition of paintings by Peter Doig, one of contemporary art’s most shoegazy painters. Here are two of the paintings Doig made in the early 1990s, the heyday of densely blurry, snowflakily-distorted, edging-towards-abstraction and almost-at-the-point-of-dissolution guitar music:

Doig’s paintings are typically based on a clearly readable figurative subject, but any subject seems to be merely an excuse for him to immerse himself in the practice and materiality of painting. Like writing a song with a proper melody and a familiar verse-chorus structure only to use it as a stable framework for all kinds of fluid experiments, adventures and disruptions in sound, tonality and texture. Doig’s works emphasise that rather than being a window on reality, painting consists of colours and shapes arranged on a surface. The way their colourful forms hesitantly caress or impudently encroach on or languorously hang down over each other can take your breath away in the same way that certain shoegaze moments can feel like the sudden plummeting of a steep coral riff under your floating diver’s body.

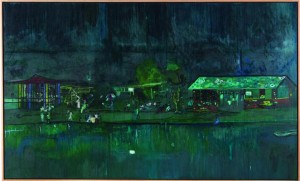

The Montreal exhibition focuses on Doig’s output since 2002, when, after living in Quebec and London, he moved to Trinidad, where he had spent his early childhood. One of the first paintings you see on entering the exhibition space reminded me of an overlooked possible addition to my post “Murky Moon” from a few weeks ago: “Music of the Future”, a hazy tonescape of dark blue and green, was inspired by Whistler’s “Nocturnes”, a series of misty, music-inspired paintings of the Thames river made by the American-born painter in the late 19th century:

Doig’s painting similarly shows a waterside scene, but instead of painting the Thames, he based his picture on a postcard he found in London of a river scene in southern India that reminded him of the Trinidad landscape. As the exhibition goes on to show, in Doig’s later paintings the earlier immersive/dreamy quality is complemented by a growing sense of displacement and of the irreparable detachment and distance felt by an outsider. It’s as if with the turn of the new millennium, his paintings started to highlight the globalized, internetted, postcolonial political dimension that can seep into the shoegaze idiom.

Doig talks about paint in the same way that you imagine Kevin Shields speaking about sound: the close-inspection fleshy/spatial details, how it drips, cascades, smears, dries and congeals on the canvas. Like an MBV song, each of his paintings creates its own tonal cosmos, rich with accumulative layers, fortuitous leaks and stains and areas of pure granulated sensuous bliss.

Peter Doig, “100 Years Ago”

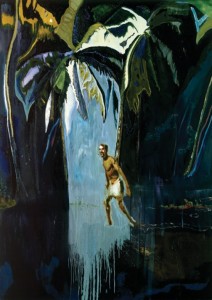

The Montreal exhibition notes suggested that in the painting “Pelican (Stag)”, a lush beach scene riven by an opaque/luminous column of light-blue paint, “the materiality of the paint is emphasized by the way it turns into a torrent of drips and dribbles at the bottom.”

Peter Doig, “Pelican (Stag)”

It reminded me of the comet-tail of guitar noise that is often left swirling at the end of shoegaze songs, or of the spilling feedback at the beginning of this song by Ride:

Images in Doig’s paintings are elusive, fading away or flickering momentarily into existence. As subtle modulations of colour blend into each other and successive layers of paint barely mask those underneath, the paintings pulsate with a shifting multitude of possible narratives, identities and perspectives.

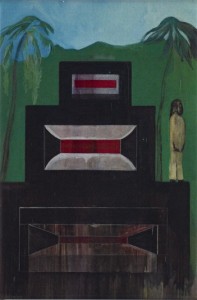

Peter Doig, “Figures in a Red Boat”

Like all good shoegaze music, Doig’s luxuriant dreaminess is underpinned by geometrical rigour and spiked with dark overtones and undercurrents. Water in his painting is both a body that connects continents, and a place to be alone in, far from the crowd in your shaky boat. Thus his position as an artist is always undermined by doubt over his belonging, knowledge and authority. The Montreal exhibition links this doubt to the postcolonial gaze, where the artist is looking at a landscape and culture that are not his own and trying to give them presence without condescending or romanticising or forgetting that he always sees this and any reality through the veil of a certain history of art and representation. We too are caught in this shoegaze web of luminosity and opaqueness, foreignness and proximity, as we inevitably experience Doig’s paintings through all the paintings we’ve ever seen, all the films we’ve ever watched and all the songs we’ve ever listened to, and probably also those we never have – yet are also touched by a unique moment of sheer amplified encounter.

Peter Doig, “Maracas”